Learn more about the “little land trust that could” and its mission to preserve the rural sea island from overdevelopment

John Girault was running on empty on an early visit to Edisto Island back in 2012, but despite the breathtaking oaks and vast marsh vistas filling up his spirit, his car still needed gas. “Where’s the nearest station?” he asked as he was leaving the Edisto Island Open Land Trust’s annual oyster roast, where he’d come to get a better sense of the conservation nonprofit that was dangling a job opportunity. “Well, son, there’s not one….You’ll have to go down the other way,” someone told him. “That’s when it hit me, ‘Wow, this place is different,’” says Girault, who ended up accepting the executive director offer (and eventually finding gas).

That was more than a decade ago, and today the island’s landscape remains largely unmarred by gas stations and convenience stores, strip malls and parking lots. The drive down Highway 174—Edisto’s main drag and one of only four National Scenic Byways in the state—feels like a two-lane trek back in time, meandering past horse pastures, wide-open fields, marshes, and waterways. Centuries-old oaks cradle centuries-old churches, while King’s Farm Market and the quaintly rustic Flowers Seafood Co. shack are the Edisto equivalent of Walmart or Publix. While many parts of the Lowcountry are beginning to be overrun by Anywhere, USA big-box blandness, Edisto is still uniquely Edisto, thanks in large part to the small but mighty Edisto Island Open Land Trust (EIOLT).

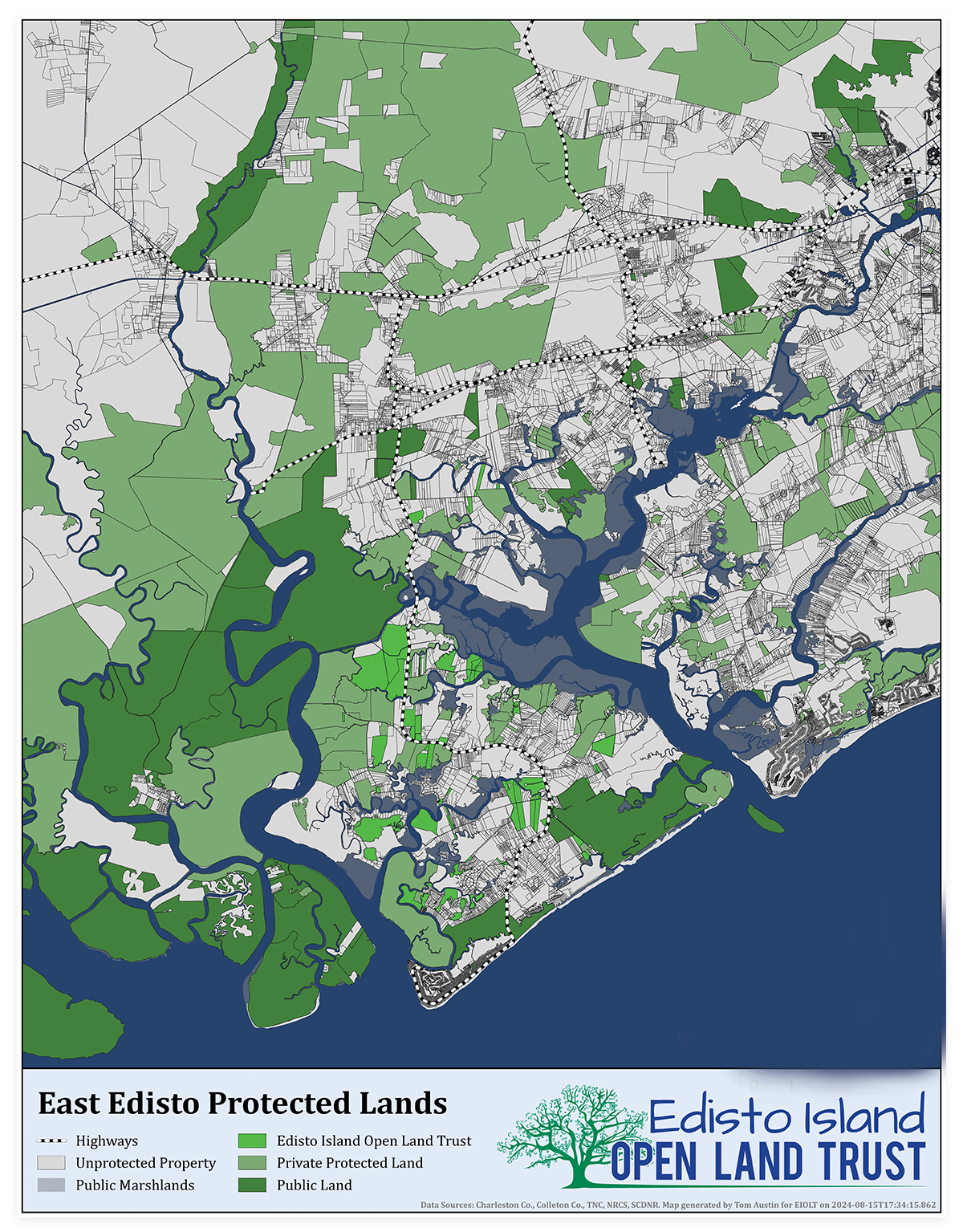

Map Courtesy of Edisto Island Open Land Trust; Data Sources: Charleston, Co., Colleton Co., TNC, NRCS, SCDNR; Map generated by Tom Austin for EIOLT April 2024

Founded in 1994, the EIOLT began as a bootstrap—and boot of a BMW—operation initiated by a handful of property owners alarmed by development pressure creeping closer and closer to the sleepy sea island. This group, including Jenks Mikell, had watched the transformation of Hilton Head to the south and Kiawah Island to Edisto’s north. A Columbia native, Mikell grew up spending summers, weekends, and holidays at his grandparents’ creekfront Edisto home on wooded property that has been in his lineage since the original Lord’s Proprietors’ land grant in 1715. It was the trunk of his old BMW that served as a roving office/file cabinet for notes from back-porch gatherings, where Mikell, Ellen and Bubba Unger, Jim Kempson, James Rice, and David Lybrand would strategize about how to keep Edisto from succumbing to a similar resort and gated-community trajectory. They had wet their feet fighting an early 1990s battle to keep a golf-course-style development from happening at Edisto’s Prospect Hill Plantation, adjacent to the ACE Basin. At the time, many of them a were also involved with the Charleston County comprehensive planning process but didn’t like the idea of county zoning solely dictating their island’s future.

Preserved In Perpetuity

EIOLT protects the environment and a way of life through a combination of conservation easements and fee-simple properties, the latter of which are owned and maintained by the organization and are mostly open to the public

(Clockwise from top left) Russell Creek Road; Paradise Shrimp Farm; Conserved lands bolster wildlife, such as these roseate spoonbills & Middletons Plantation.

Punching Above its Weight

Inspired by the ACE Basin conservation successes abutting (and later including) Edisto Island, the group resolved to take matters into its own hands and kicked in a few thousand dollars each to start their own land trust. They borrowed bylaws from the Beaufort County Open Land Trust, the state’s first land trust (EIOLT would become the third, after Lowcountry Open Land Trust). “We recognized that we, those who loved Edisto and lived and worked here, needed to do this ourselves,” says Mikell, a long-standing board member. With a meager budget and no staff, the nascent EIOLT embraced its mission: “to give leadership in preserving, protecting, and enhancing the natural beauty and open vistas of Edisto Island.” Early gains included David Lybrand’s donation of 400 acres of predominantly marsh that would help preserve the viewshed as one crosses onto the island. EIOLT’s first outright purchase—a mere two acres near the Serpentarium—was a small but strategic gain to help protect Highway 174’s undisturbed vista.

The young nonprofit made slow but steady progress; its membership roster grew to 150 people by the end of 1995, and they were gaining support—and a few conservation easements—from like-minded landowners. Still, it would be nearly a decade before EIOLT brought on its first full-time executive director, a hire that proved monumental, according to Mikell and Ellen Unger. Marian Brailsford’s productive tenure secured EIOLT’s reputation as “the little land trust that punched above its weight,” says Girault.

Brailsford and her husband had fallen in love with Edisto after owning a vacation home there for years, then eventually moved full time to the island in 2002. She joined EIOLT’s board in 2003, bringing a get-it-done mentality thanks to years of experience as a successful sales trainer and consultant. Shortly after joining the board, the then-part-time director resigned and Brailsford agreed to step in “temporarily”—a stopgap that morphed into a full-time, paid position lasting nearly a decade. “It was still early in the national land trust movement, but people were starting to catch on,” Brailsford says. Plus, the work was “a lot more fun” than her business consulting.

“Marian was a spitfire,” says Unger, a founding EIOLT board member. Brailsford’s accomplishments include spearheading the National Scenic Byway designation for Highway 174, overseeing a laborious national land trust accreditation process, and inking easement agreements right and left, including critical and complicated properties like the 505-acre gateway parcel known as Paradise Shrimp Farm, where a marina, luxury home development, and condominiums had been proposed.

In the fall and summer of 2007 alone, Brailsford completed 11 land protection agreements totalling 1,657 protected acres. In 2009, EIOLT was officially invited to join the ACE Basin Project, which Brailsford called “a dream come true, not only because it will increase the credibility it lends our organization, but also because it will increase the pace of conservation on Edisto Island.” By the time she stepped down in 2011, nearly 50 percent of Edisto Island had been protected.

Community-Minded

Beyond conservation easements, EIOLT protects the natural environment through ongoing educational programs for both children and adults

(Clockwise from top left) The Young Naturalists program teaches fourth-through-eighth-grade students about environmental stewardship through hands-on activities, such as beachcombing and crabbing; An expert-led butterfly walk in the Francis Marion National Forest; Back to Nature learning series for adults engages residents with the habitats, wildlife, and heritage of Edisto, including building an oyster reef at Roxbury Park in partnership with the SC Department of Natural Resources.

Expanded Outreach

Though at the time he didn’t know much about Edisto, Girault, formerly the director of the East Cooper Land Trust, met with Brailsford several years before he took over EIOLT’s helm. “I was new in the conservation space and eager to learn all I could from local leaders,” he says. “Word was out about Brailsford. She had put EIOLT on the map, and its reputation, even nationally, was growing.” Girault, who was appointed executive director in 2013, has further catapulted the organization’s profile, but with so much of the island already protected, he’s worked to broaden the organization’s outreach in innovative ways. The Charleston County Greenbelt funding that had fueled much of the region’s conservation activity was beginning to sunset, and there were only a few land deals in the hopper when Girault came on board. “But this place was still fragile. We needed to pivot, diversify our base, and find new projects beyond land conservation to keep the community educated about why Edisto is special and needs protection,” he says.

Longtime EIOLT supporter Melinda Hare expanded the ongoing Young Naturalists program that began as an after-school initiative for local children and evolved into a partnership with Green River Preserve in the Upstate, allowing EIOLT to send six middle schoolers each summer for a nature-immersed camp experience. Girault brought on wildlife and fisheries biologist Tom Austin, whose family has deep roots on Edisto, to oversee all easement monitoring and stewardship. His role quickly expanded into that of a full-time land protection specialist.

The land trust grew out of a desire “to keep Edisto Edisto, and Edisto has always been more than just the dirt, the land. It’s also the people, culture, and history,” Austin says. Along with the board and a staff that now includes outreach coordinator Denzel Wright and young naturalist coordinator Krystal Parsons, Girault and the board have been “exploring more paths that lead to the same goal,” he adds. One of those paths leads through waist-high grass in the former cotton fields surrounding the Henry Hutchinson House, a circa-1885 farmhouse off Point of Pines Road that is one of the region’s last remaining Reconstruction-era homes built by a formerly enslaved freedman. When Girault first saw the long-abandoned house, it was barely standing, but he understood its gravitas within the community, the deep layers of Edisto’s history hidden under its crumbling eaves. He organized a funding campaign enabling EIOLT to purchase the house in 2016 and protect its surrounding acreage. “It needed to be saved,” says Girault. “We jumped on it because no one else was.”

The land trust initially raised $275,000 to stabilize and begin restoring the house, with the goal of creating a community gathering place and educational site. In March 2023, EIOLT received a $950,000 Mellon Foundation grant to support the interpretation of the site, including research and exhibit installation, programming, and the hiring of Sarah Stroud Clarke as the Hutchinson House’s full-time director. “It’s transformational, a true game changer,” says Girault of the Mellon Foundation funding, that—along with the National Park Service bringing the Hutchinson House into its Reconstruction Era National Historic Network—gives EIOLT the opportunity, and responsibility, to honor the legacy not just of the Hutchinson family, but the broader African American community on Edisto.

Restoring Local History

On a mission to preserve the Recontruction-era Hutchinson House and tell its story

(Left to right) The son of a freedman, Henry Hutchison built the house, pictured circa 1900, for his bride, Rosa. The place was passed from generation to generation until the last Hutchinson moved out in the 1980s; Working with Hutchinson family descendants and the Lowcountry Conservation Loan Fund, EIOLT purchased the house and adjacent acreage in 2016 and began raising the money to prevent its collapse and restore it; The house this summer; the last phase of the restoration is estimated to be complete by the end of the year with an opening date anticipated in spring 2026.

Holistic View

Restoring and operating a historic house site is not something Girault expected his small conservation nonprofit would be doing, nor is it mission creep. “Our holistic approach embraces community conservation,” he explains. When the Edisto Island Youth Recreation program needed a place for practice fields, a gym with basketball courts, and multiuse spaces for both kids’ sports and adult recreation (the closest public facilities are 20 miles away), EIOLT wrote the grant application that helped the program secure 145 acres—land that is primarily farmland, crisscrossed with wetlands, and bordered by a mature forest with abundant wildlife habitat. “They needed land, we protect land,” says Austin. “Community conservation is when a land trust helps bridge the gap between the needs of the environment and the needs of its community to work towards a mutually beneficial project.” It’s a win-win: in this case, Edisto Island Youth Recreation gets new facilities, including a library and wildlife trail, while EIOLT protects critical habitat.

Now at age 30, EIOLT is in full stride working on numerous fronts to “keep Edisto, Edisto.” They’ve protected 4,218 acres, including 42 conservation easements and counting, representing 52 percent of the island. In the face of climate change and sea-level rise, however, the threats are no longer coming primarily from developers. Saltwater inundation of marshes, marsh migration, and water-quality impacts of Edisto’s ubiquitous septic systems are among the issues the land trust is now focused on, including the development of an Edisto Watershed Plan. This year, two-term board chair Bob Hare, who also serves on the Watershed Plan advisory group, formed an environmental committee to address climate-related concerns.

Meanwhile, EIOLT continues to collaborate and partner with the other key players in the coastal conservation realm and more broadly, including coordinating and strategizing alongside The Nature Conservancy, Lowcountry Land Trust, Open Space Institute, and others. In addition, support and collaboration remains strong with county agencies and groups, and with the ACE Basin Task Force. “Lowcountry conservation is a team sport, it’s our secret sauce,” says noted conservationist and ACE Basin leader Charles Lane. “Edisto is a critical part of the ACE Basin, and EIOLT is an active participant working with landowners, other conservation groups, and state and federal wildlife agencies to protect it. Today, Edisto Island is what all the sea islands used to be, thanks to EIOLT’s leadership in keeping it rural.”

“We’re grateful to have so many committed partners who share our vision for more green space and land protection throughout the Lowcountry,” adds Girault. “I think we all understand how vulnerable and how interconnected our region is, and that we’re all stronger and more effective when we work together.”

Learn more about the Henry Hutchinson House here.

WATCH: The restoration of the Reconstruction-era Hutchinson House

Photographs courtesy of Edisto Island Open Land Trust; Alice Keeney; Vanessa Kaufmann; (Brailsford) David Edwards; (Sand Creek Farm) Vanessa Kaufmann; (Paradise Shrimp Farm) Abi Locatis-Prochaska, (Spoonbills) Tom Austin; (Newton Frogmore) Charleston County Greenbelt Programs; (Wright & House now) Alice Keeney; courtesy of (house circa 1900) Hutchinson Family Private Collection